-

Winfred RembertWhite Gold, 2017Acrylic paint on carved and tooled leather67.8 x 86.4 cm (26 2/3 x 34 in)

Winfred RembertWhite Gold, 2017Acrylic paint on carved and tooled leather67.8 x 86.4 cm (26 2/3 x 34 in)

Framed: 81.8 x 100.2 x 4.4 cm (32 1/4 x 39 1/2 x 1 3/4 in) -

-

PARTICIPATING ARTISTS

-

WINFRED REMBERT

b. 1945 – d. 2021 -

At the age of 51, Winfred Rembert began chronicling his harrowing experiences of oppression, persecution, and political struggle in the Jim Crow South. Painted on carved and tooled leather, reclaiming a craft he learned in prison, Rembert’s oeuvre materially evokes the ways that, in the words of PTSD expert Bessel van der Kolk, "the body keeps the score".

White Gold (2017), a highly patterned surface with alternating rows of colorfully dressed workers and bold white cotton balls, plays with the line between visibility and obscurity.

-

Winfred Rembert

White Gold, 2017Acrylic paint on carved and tooled leather

67.8 x 86.4 cm (26 2/3 x 34 in)

Framed: 81.8 x 100.2 x 4.4 cm (32 1/4 x 39 1/2 x 1 3/4 in) -

-

Chain Gang Picking Cotton (2011), a tightly cropped landscape of winding black and white and green bands, play with the line between visibility and obscurity.

In his Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir Chasing Me to My Grave, Rembert wrote, "People...don’t recognize those stripes as people until they take a real good look. That was my goal—to put it down so you couldn’t understand it until you take a real up-close look. That tells you something about prison life."

-

Winfred Rembert

Chain Gang Picking Cotton, 2011Acrylic paint on carved and tooled leather

79.5 x 86.3 cm (31 1/3 x 34 in)

Framed: 94 x 102 x 5.1 cm (37 x 40 1/7 x 2 in) -

-

Winfred Rembert

The Attack, 2018Acrylic paint and marker on carved and tooled leather

54.6 x 32.4 cm (21 1/2 x 12 3/4 in)

Framed: 69.8 x 46.9 x 3.8 cm (27 1/2 x 18 1/2 x 1 1/2 in) -

-

As a young man, after being attacked during a peaceful Civil Rights demonstration in Georgia, he fled in a stolen car, illustrated in The Getaway (2015), only to be arrested and thrown into jail. After a year without charges, Rembert managed to escape, but was caught, put inside the trunk of a police car, and narrowly survived a lynching before being sent back to prison and sentenced to hard labor.

-

Winfred Rembert

The Getaway, 2015Acrylic paint on carved and tooled leather

82.5 x 50.2 cm (32 1/2 x 19 3/4 in)

Framed: 97.8 x 64.8 x 5.1 cm (38 1/2 x 25 1/2 x 2 in) -

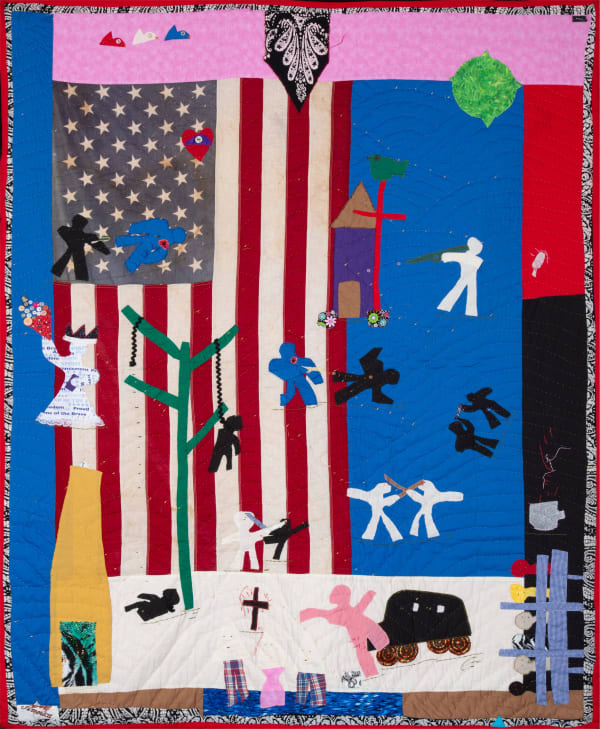

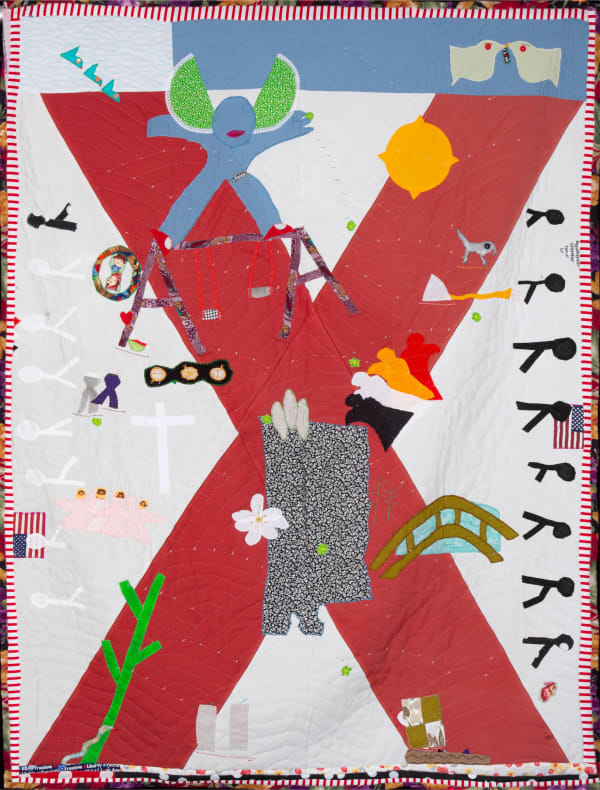

YVONNE WELLS

B. 1939 -

Yvonne Wells, a long-time educator in the Alabama Public School system, is known for her didactic 'story quilts' that uniquely meld geometric abstraction and bold figurations.Replete with biblical iconography, and historical imagery, her works highlight Alabama's fraught racial past and America’s ongoing struggle for equality and justice.

Quilting, long associated with women's work and the domestic sphere, and the artist’s preferred pastel colorways, serve as a compelling foil to the sobering histories of violence enacted against, as well as the triumphs of African Americans in the pursuit for equal rights.

-

Yvonne Wells

Good Trouble - John Lewis, 2023Assorted Fabrics

208.3 x 213.4 cm (82 x 84 in) -

-

-

-

-

In her epic 12-part work Two Accusers, Nine Accused (2014), Yvonne Wells engages the infamous story of the Scottsboro Boys, one of the most notorious miscarriages of justice in American history.

Arranged in a grid formation, a title panel flanked by saccharinely sinister likenesses of the two female accusers sit above nine, hagiographic portraits of the young men, their names and ages scrawled carefully across their necks. Above each of their heads, three birds fly in a line to signify the Christian holy trinity, symbolizing the artist’s faith and eternal sanctity of human life.

-

Yvonne Wells

Two Accusers, Nine Accused, 2014Assorted fabrics

12 parts

Overall: 245.1 x 200.7 cm (96 1/2 x 79 in) -

-

ISABELLE ARMAND

-

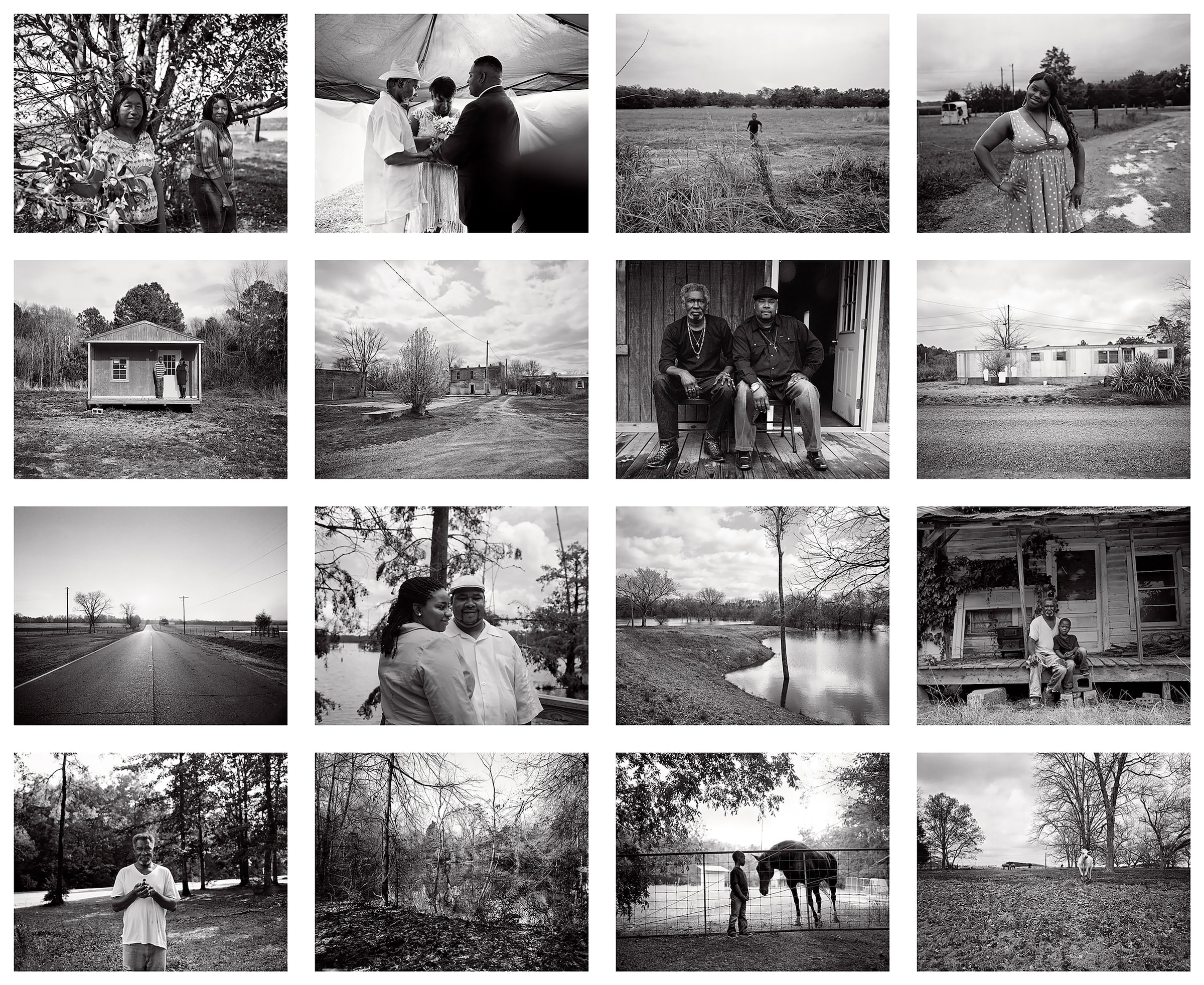

Working across analog photography and film, Isabelle Armand’s projects seek to make visible the oft-overlooked lives, cultures, geographies of the disenfranchised.

The twenty-five monochromatic photographs, exhibited here for the first time, center on Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer, two men from Noxubee County, Mississippi, who in the early 90s were wrongfully convicted of murders they did not commit, based on pseudoscientific forensic evidence. The men collectively served more than 33 years of these sentences before the Innocence Project successfully took on their cases resulting in their exoneration in 2008.

-

Isabelle Armand

Photography Grid 1, 2013 - 2018Archival UV on dibond

16 parts

Each: 20.3 x 25.4 cm (8 x 10 in)

Each framed: 22.2 x 27.2 x 3.6 cm (8 3/4 x 10 3/4 x 1 1/2 in) -

-

Excerpted from a larger body of around seventy images captured over a span of five years, Armand spent extended periods living alongside and photographing the men and their families against the rural Mississippi landscape to which their history is inextricably tied.

Arranged in two indexical groups, Armand’s intimate images demonstrate the resilience and optimism of the Brooks and Brewer families as they reclaim the narratives of their lives, while simultaneously confronting the viewer with the knowledge that these images might never have been taken had justice not (belatedly) prevailed. Alternating between intense chiaroscuro and icy grayscales, the photographs appear both timeless and imbued with the lost years of Levon and Kennedy’s incarcerations.

-

Isabelle Armand

Photography Grid 2, 2013 - 2018Archival UV on dibond

9 parts

Each: 25.4 x 20.3 cm (8 x 10 in)

Each framed: 27.2 x 22.2 x 3.6 cm (10 3/4 x 8 3/4 x 1 1/2 in) -

-

Over the course of the 20th century, modern prison life creeped away from associations with hard labor, toward the more insidious, though equally brutalizing characterization of “hard time”. As the scholar Jackie Wang notes, while temporal punishment may seem more humane, as it does not leave visible wounds, psychic pain and physical pain share the same neural circuitry.

-

Subscribe Newsletter

Be the first to know about new exhibitions, artist updates, as well as books and more. Sign up for our newsletter below.